I've written in the previous posts about my experience studying visitor behavior at zoos. Well, I've briefly mentioned it, at least. Although many zoos throughout the U.S. are studying visitor behavior, it is a rare occasion for designers to get the chance to get the first-hand experience of studying how visitors use their designs.

I highly recommend doing some informal visitor studies at exhibits you've designed as well as at those you have not. From my past visitor studies, I've learned two consistent lessons:

1. Visitors stay at each viewing station less than 90 seconds. No matter what species is displayed, or how well they are displayed. The only exception is when the animal is extremely active. For example, studying visitors at Disney's Animal Kingdom's beautiful tiger exhibit, I noticed a major spike in visitor length of stay, from the average 90 seconds to upwards of 9 minutes when the tigers had, serendipitously, spotted a rabbit in their enclosure and subsequently went into hunting mode. The experience was mesmerizing, and everyone was swept up into the excitement. This makes me wonder if live feedings shouldn't be more acceptable...but that's another story.

2. Less than 2% of visitors fully read signage. Fully interactive interpretives may be a different story. None of the exhibits I have studied had any of these more modern interpretives.

Researchers at Chicago's Lincoln Park Zoo studied visitor behavior following the opening of their recently opened Regenstein Center for African Apes. The article written outlining their experience supports only one of my lessons...No one reads signs. However, their visitor stay time far exceeded anything I've encountered (although they measured their length of stay differently, by measuring the full exhibit stay time rather than per viewing window).

That researcher in the ape house? She was studying you.

By James Janega

Tribune staff reporter

April 26, 2007, 10:57 PM CDT

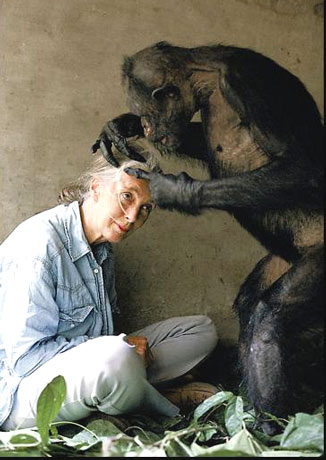

The animal behaviorists at Lincoln Park Zoo have given simple tools to gorillas and taught chimpanzees to navigate computer touch screens, but their latest experiment involved a primate so intelligent and cagey, it was going to take work to outsmart it.

The subject was people and to measure their behavior at the zoo's ape sanctuary without them catching on, a 24-year-old zoo office worker with girl-next-door looks would have to slip on quieter shoes, wear muted colors and follow people in secret by watching their reflections on glass.

Starting last spring, conservation assistant Katie Gillespie spent a year clocking visitors' stays in the Regenstein Center for African Apes, noting where people loiter and what they look at.

With her boss, Steve Ross, she frowned when people ignored interpretive signs and took smug comfort when subjects were captivated by apes. For months, she and Ross hoarded statistical glimpses into how humans prefer to learn about chimpanzees and gorillas.

It was all very scientific, not to mention fun and kind of sneaky.

In the course of 476 observation sessions over 12 months, Gillespie and Ross learned that everybody likes watching apes and nobody likes reading signs. They found people love to pose with ape sculptures, and that parents all too often make up answers for their children.

And they proved the best way to fool people is to let them fool themselves.

"I've had people ask me what I'm doing," Gillespie said. "I tell them I'm taking behavioral data. Then they ask me questions about the animals."

Gillespie, who has a bachelor's degree from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, trained in natural resource management and has a day job as exotic as her office cubicle.

As for zoo experience, she made signs for a raptor walk at the Marshfield Zoo near Wausau. Her real job at Lincoln Park Zoo involves administrative tasks at an office a few minutes away from the ape building.

But on Feb. 21 last year, she climbed into an unlit, concrete mezzanine at the Regenstein Center, looked out windows tailored for watching animals, and listened as Ross told how to follow people without them knowing.

It was a slow morning in the ape center, a tough time to avoid notice. But there are tricks of the trade, Ross reassured her.

Downstairs, other conservation assistants were using Palm Pilots to study apes. Hold one, and people will assume you're watching chimps, he said. Get ahead of people and let them pass you. Use reflections and peripheral vision.

He used the word "spy." Gillespie got the job after biologists told Ross they'd rather watch apes, not people.

Ross had done this before, in 2000, but inside the old, round, dark Great Ape House, a cinch compared with the Regenstein Center's bright, open floor plan. This new place, built in 2004, upped the ante. You could get caught.

"I've had an awful time getting people to do this," Ross told her.

Gillespie stuffed printed explanations of the study in her pocket that included Ross' phone number, to hand out in case she was confronted. In those first days, she wondered if it was going to work.

"It's almost impossible," she exclaimed early on. As a practice subject approached the entrance, she hurried down the metal stairs to the floor below, her high-heeled pumps clanging on each step. The ringing subsided just as the subject opened the door below the mezzanine.

"We gotta get you some sneakers," Ross told her later.

By May and June, when school groups crowded the floor so thoroughly it was hard to move, Gillespie was an expert. She followed kids in camp groups in July, vacationers in August and September, and aborted an observation only once-when a young couple started making out.

It turned out the challenge wasn't getting caught, she found. It was battling exasperation. People complained when the apes sat around, in the middle of rest cycles clearly defined on nearby signs. Parents made up answers to kids' questions. People made mistakes, and no one corrected them.

"You hear people asking questions that are written all over every sign everywhere," Gillespie said of those moments. "But you can't influence them."

So she just observed-always the fifth person to enter after the last subject left. The sessions were always anonymous. Regulars were ignored.

Her shortest follow came on a sunny Sunday afternoon in June: a girl in an organized group who stayed 2.3 minutes while a heavy crowd shoved through the air-conditioned building. The longest visit was in December, a woman with children who relaxed for 116 minutes. January brought visitors in a steady, unhurried rhythm. Often, the subjects stood at Gillespie's elbow without knowing.

One was the man in the blue coat. At midday on Jan. 24, 2007, Gillespie, wearing moccasins, padded down the stairs from her mezzanine perch to beat him to the chimp enclosure.

Behind her, the man watched JoJo's gorilla troop, then breezed past an interpretive display to study Hank and his group of chimps, where he planted himself in front of Gillespie to do it.

She wore a zoo badge and appeared to watch the animals. Every 15 seconds, her Palm Pilot chirped a reminder to note the man's behavior: "Locomote," "Watch Chimps," "Photo Chimp."

The terminology was borrowed from animal behaviorists, and the man in the blue coat had no idea the soft beeping was for him.

Over 29 minutes, Gillespie took two pages of behavioral notes. The man watched both gorilla troops, talked to docents, took more pictures and left. The list recorded only movement, location and activity.

But on the floor it looked like more. It seemed like deep fascination.

A full analysis is months away, but some things are clear.

Watching apes was the most popular behavior, and visitors lingered more in the airy naturalistic environment than in the previous concrete-and-steel building.

The most popular exhibit elements were life-size hands and busts of various apes, which people touched and photographed regularly. The average visit was 15.5 minutes.

But many zoo interpretive standbys fell flat. Just about everyone ignored a looping video describing behavioral research on apes at the adjoining Lester E. Fisher Center. They likewise ignored graphics beside actual apes that described a "day in the life" . . . of apes.

People learned by watching apes that acted as they do in the wild.

It was an epiphany for Gillespie that came on one of her last observations. In February, a young mother brought her 1-year-old daughter to the chimp enclosure where Kipper, a young male, showed off for the girl through the glass. The mother and daughter were delighted by the connection.

"You knew that this was such a special moment that they would remember," Gillespie said. "And maybe that would be more impactful. Even though they weren't reading signs."

jjanega@tribune.com Copyright © 2007, Chicago Tribune

I fully believe every time a new exhibit is proposed, designers should spend at least one day watching how visitors use the old exhibit, and / or similar exhibits (to that proposed) at other zoos. Additionally, we need to instate an industry standard of post-opening visitor behavior research. Most institutions do some amount of study post-opening, but that information is rarely passed onto the designers. Designers need to be proactive and spend some time at their creations, truly critiquing the successes and failures. Only then will we be truly able to truly be experts.

"In an ideal world chimpanzees and monkeys would be out in the wild as they were intended to be. But in the real world, there are not so many places like that and they are getting smaller all the time.

"In an ideal world chimpanzees and monkeys would be out in the wild as they were intended to be. But in the real world, there are not so many places like that and they are getting smaller all the time.

Here

Here